Interview: GRANT FOSTER

Ceri Hand Artist, Interviews, Painter

I first encountered Grant Foster's work in 2008, in the John Moores 25 painting prize exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. I was happily haunted by the gnarly, tragi-comic, skeletal, uniformed, character depicted in his painting Hero Worship (2007). I was especially delighted that Grant looked and sounded exactly like the artist that was meant to paint it.

I first encountered Grant Foster's work in 2008, in the John Moores 25 painting prize exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. I was happily haunted by the gnarly, tragi-comic, skeletal, uniformed, character depicted in his painting Hero Worship (2007). I was especially delighted that Grant looked and sounded exactly like the artist that was meant to paint it.

A couple of years later painter Eleanor Moreton recommended Grant for a group show I curated with artist Matthew Houlding Memory of a Hope, at my gallery in Liverpool. Grant rocked up with a couple of paintings under his arm, including Relic (2008), another spook with eyes made from found coils of braided hair, a gouged hollow for a nose and a Joker-esque red grin. The other comparatively delicate painting, carved out of mustard yellow beeswax, of a melancholic muse Beauty is Not Compassionate Towards You reflected his thirst for knowledge of what painting can do and his refusal to back himself into a corner.

Grant is an intensely bright, political, considerate, and playful artist, unrelenting in his determination to reveal the complex web of systems, images, language, and hypocrisy that shapes us and that rains down upon us daily. He makes viewers really work for it. Lurching from fine, barely-there delicate colourful wisps and washes, to chewy, densely whipped knots of oily bleakness, he pushes and pulls at memory, and the limitations of painting to test the blurring of coercion, power, impotency, and submission.

Grant Foster (b.1982, Worthing), is a London based artist who completed an MA in Painting at the Royal College of Art in 2012. Foster’s recent selected exhibitions include: I’m Not Being Funny, Lychee One, London, 2019; Trade Gallery, Nottingham, 2018; Ground, Figure, Sky, Tintype Gallery, London, 2017; Popular Insignia, Galleria Acappella, Naples, 2016, Salad Days, Ana Cristea Gallery, New York, 2015; Holy Island, Chandelier Projects, London (2014); Bloomberg New Contemporaries, Spike Island and ICA; (2013-14). In 2019 he was the Randall Chair at Alfred University New York, 2019; Fellow in Contemporary Art with The British School at Rome, 2019; and a Prize-winner in John Moores 25, 2008.

I'm Not Being Funny, installation view, Lychee One Gallery, London, 2019

What are you doing, reading, watching or listening to now that is helping you to stay positive?

My partner works as a doctor in a hospital, so our experience has been a little different perhaps. Between the reality of her experience and the situation as its unfolded publicly, the small things in my daily life took on new meanings. I would take extra care making breakfast and found new pleasure in mind-numbing chores. At the height of lock-down it started to feel as if we were communicating with our cats in new ways – which obviously sounds absolutely insane. Yet those small duties went some way to mitigate the white noise from outside.

What are you working on and how has the lockdown affected your ideas, processes and chosen medium?

I think artists are good at being able to adapt – it was clear that lockdown was coming in some form or other – so I made preparations to work temporarily from home. Once I was able to focus on making work, I got into a new rhythm of working, which ran alongside all the domestic stuff you have to do.

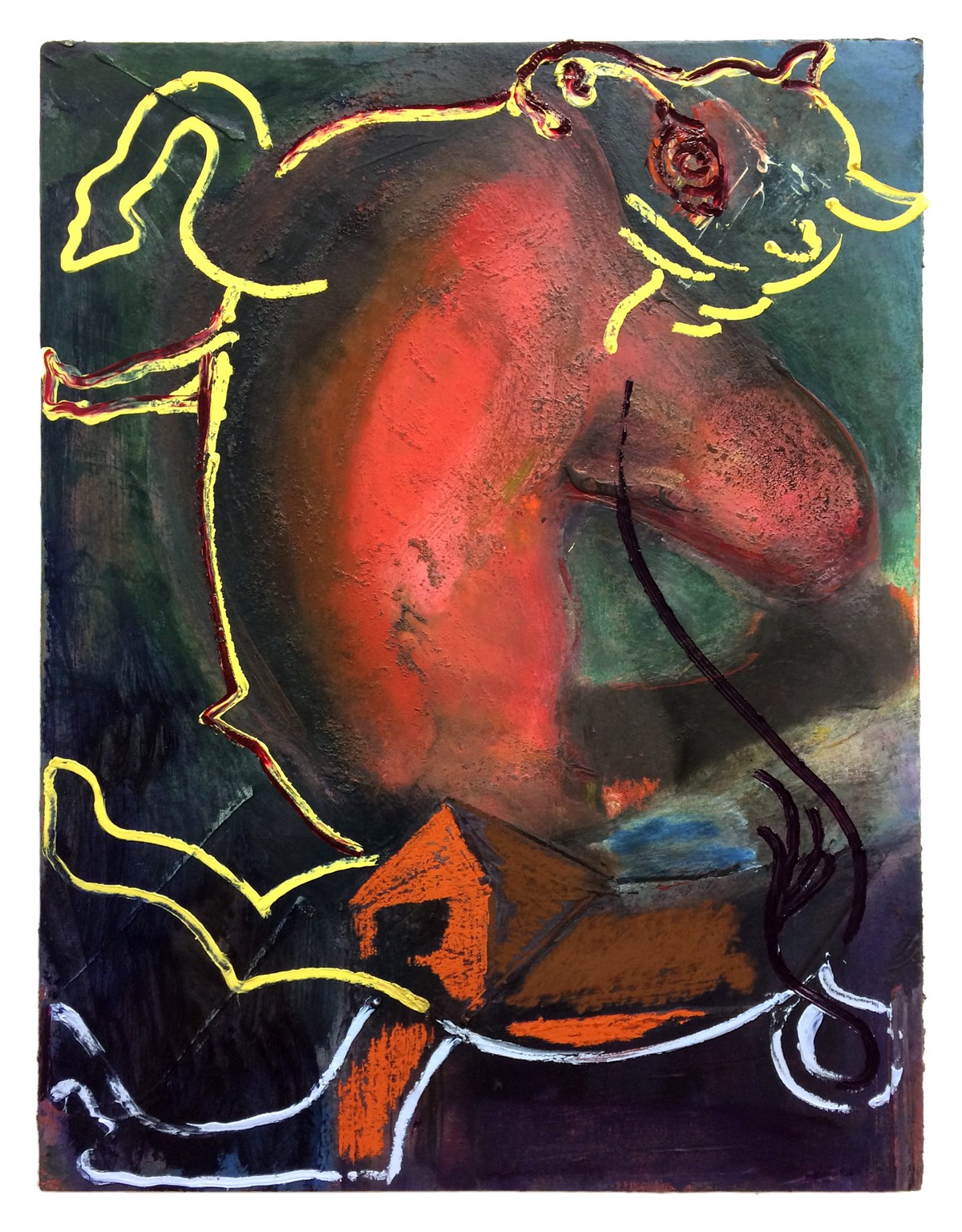

I’ve been making work on paper, which at the time is very automatic and when I look back at them, they have distinct themes. There’s a motif of a worker that has kept re-appearing over time and now this figure has become more disembodied perhaps. I’ve also been looking at the things that surround me more. We were given a wonderful model of a human-come-pig-head as a wedding present – so he’s been popping into my imagery! Once I was able to return back to the studio, I’ve been painting with what feels like a renewed rigor, perhaps as a consequence of this moment of reflection.

I’ve also started to collaborate with some old friends to make music – we started this before the lockdown but have been able to devote more time and energy to it. This is one the things that the last few months has shown – is that, once you take the vampiric shit out of everyday life, there’s still a decent amount of time in a day.

The Rat King 1576, 2020, Acrylic oil and oil stick on canvas, 182 x 147cm

What do you usually have or need in your studio to inspire and motivate you?

Normally a sense of calm – and a clear head, which is weird as my more recent paintings can appear quite frantic - I’ve got a postcard of Piero’s, Baptism of Christ which I’ve had for a long time now – it’s an astonishing image of stillness that I like to look at.

What systems, rituals and processes do you use to help you get into the creative zone?

I like sweeping my studio floor – I’m not really sure why but I find it terribly calming.

What recurring questions do you return to in your work?

We have a very binary attitude in the wider world, we think in terms of systems such as cause and effect – and I don’t think that offers us the full picture – art can exist in place between knowing and not knowing. I try to create processes within my work where I am forced to re-assemble my intentions – and I hope there can be opportunities for art to grow within those cracks.

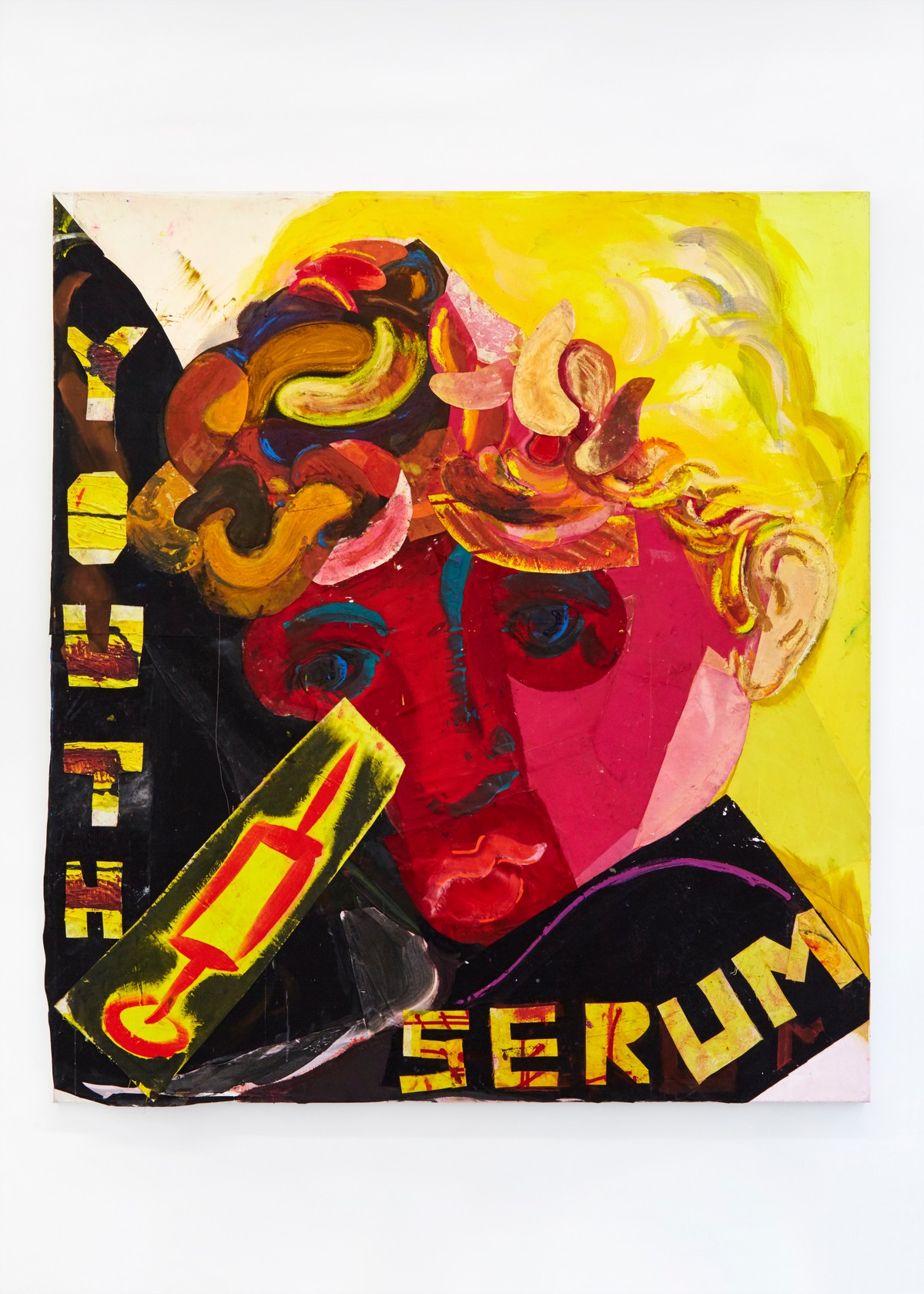

Youth Serum, 2018, Glue, oil stick and pigment on collaged canvas and Polyester, 95 x 177cm

What do you care about?

I’m not being flippant when I say the future. It’s obviously becoming clear how the shape of things to come is going to be defined by our collective actions over the coming years. We have the potential to travel along a number of wildly varying tangents, each of which are drastically different to where we are now. It’s impossible not to be concerned about this.

What risks have you taken in your work that paid off?

I’m an itchy type of artist – and have changed appearances over the years. For me painting is a balancing act between material exploration and subject – and I’ve allowed myself the opportunity to follow where the material leads the work, seeing how that corresponds with the subject. For me, art is a verb – it’s an act of doing, in this way the act is democratic – and the to do, implies freedom and there’s strength with that.

My last solo exhibition felt like a departure from what I had shown previously. I wanted to bring something raw and direct back into the work – and had become interested in the methodology of collage as a way into this. I’d been making a large number of paper-works at the time, with collage acting as a natural way for me to resolve an image on a smaller scale. I developed an interest in coloured fabrics and pre-staining canvases, thinking I would use these materials instead of mixing paint more conventionally on a palette or in a pot.

I wanted the work to communicate, through the anxiety and indecision of making it if you like, that there is a sense of empathy with that process. The way I was working at the time –with these collaged forms, felt very open ended as there were countless variations of an image to consider. It was this sense of open-endedness that offered me a new set of possibilities which I’m still processing.

Torments of The Worker, 2020, Acrylic, ballpoint pen, correction fluid, pencil, crayon, Letraset and marker-pen on Sotheby’s Merger Paper, 27 x 20cm

What risks have you taken that perhaps did not go so well but you learnt the most from?

I think my biggest problem (there are many to choose from!!) is that I’m naturally inquisitive regarding materials – and as a consequence this may have seduced me into sacrificing the psychological depth that can come about through really pursuing a given material with singularity.

Everyone for Themselves and God Against All, 2016, Crayon, charcoal, pigment and glue on canvas,100 x 70cm

What is your favourite exhibition you have participated in and why?

It was one of the first shows I did in 2006. Some friends and I put on a painting exhibition in the warehouse unit I lived and worked in at the time – we painted the floor grey the night before, printed out fliers, bought the drink in – and invited everyone we knew. There was a real sense of innocence to it that I still value now.

What would you hope that people experience from encountering your work?

I am concerned by a tendency that considers ambiguity a weakness or as something that needs combating. I would suggest precisely the opposite, that it is because of this moment we’re in, where nuance has been continually derided by not only our political class but by the information and communication systems we have become accustomed to – that imagery, art, ideas and culture in its broadest sense – this is the realm where nuance and ambiguity must be allowed to endure, in order for us to learn how to move forwards.

I Work for You, You Work for Me, 2016, Glue, paper, pigment on canvas, 195cm x 185cm

Could you tell us a bit more about at a time when you felt stuck and what you did to help yourself out of it?

Writing has always helped me to find a way around problems which aren’t necessarily logical or with a fixed exit. My brain has a tendency to veer toward extremes – and I find writing a decent way to navigate between two poles.

Measure by Measure, 2017, Bleach, charcoal, glue, oil stick and pigment on collaged canvas, 150 x 115cm

What kind of studio visits, conversations or meetings with curators, producers, writers, press, gallerists, or collectors do you enjoy or get the most out of?

Generally speaking, I enjoy people coming to the studio – as that’s really where they can see the thinking – and doing, that goes into the work. And it’s where I can gauge how we might get on, by the way they look for a paint free spot to drop their belongings!

Do you have a trusted muse, mentor, network, or circle of friends you consult for critical feedback?

Naturally there are a few people I gravitate towards where we share a sense of trust.

Which artists or creatives do you feel your work is in conversation with?

There are lots to list! But more recently through the music I’ve been listening to I’ve become interested in the idea of layering images – and how associative flows can affect our perception of the world. The early albums of Cabaret Voltaire did something similar with the repetition of collaged tape-loops. To me, there’s a connection between those auditory analogue experiments and the associative, almost hallucinatory flow of Francis Picabia’s Transparencies paintings. I’m becoming more and more interested in how images layer upon one another and what this can offer – in a similar way perhaps, to how one may connect seemingly incongruous phenomena, such as the patterns on a wall or apparently random noises.

The Beast with Two Backs, 2020, Oil and pastel on panel, 80 x 60cm

How do you make money to support your practice?

Through a bizarre combination of tech-work and luck.

What compromises have you made to sustain your practice?

Money, health, self-worth – being an artist is a joyous game of masochism.

What advice would you give your past self?

Don’t try and please everyone, Grant.

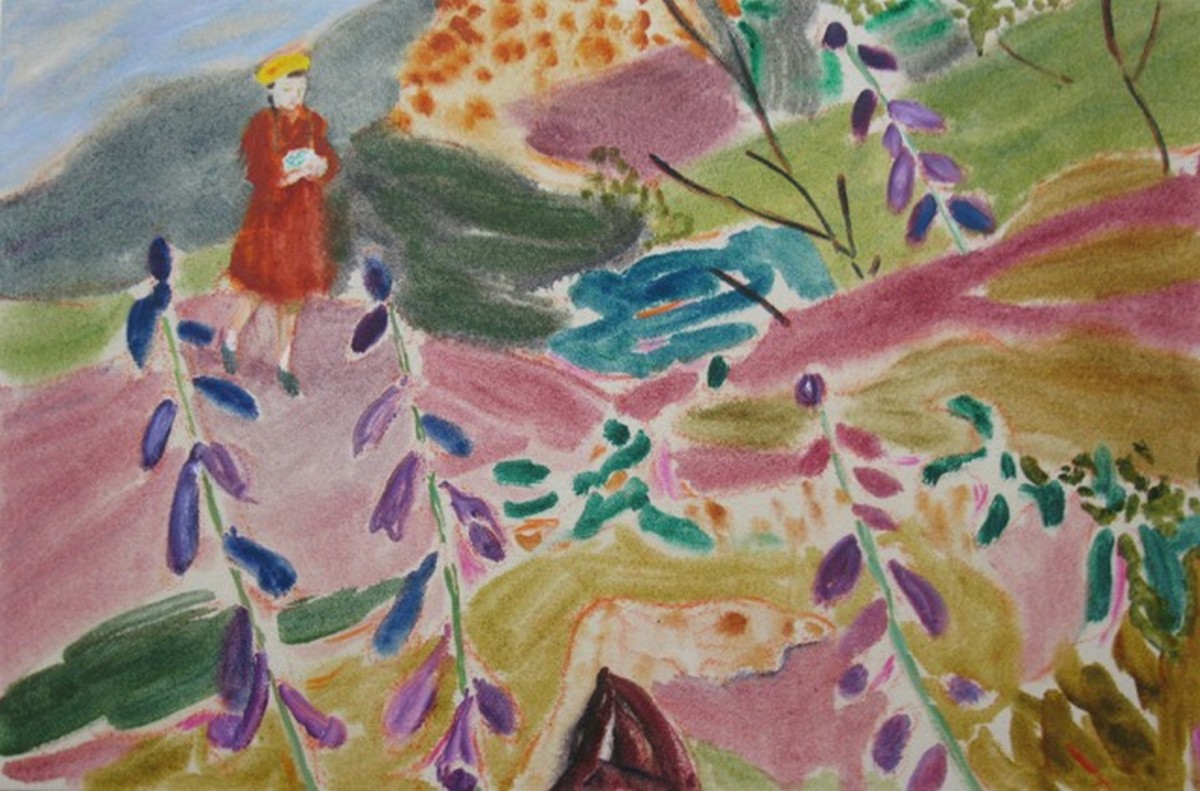

Beauty Boys, 2019, Acrylic and charcoal on collaged paper, 57 x 76cm

Can you recommend a book, film, or podcast that you have been inspired by that transformed your thinking?

One of my closest friends put me onto The Weird Studies podcast, which is based around art and philosophy – and it’s the best one I’ve come across so far.

Follow Grant on Instagram @foster_grant or visit his website

Follow his gallery @tintypelondon on Instagram and website Tintype Gallery

Please share this interview

And do feel free to email or contact us via socials @cerihand

Coming Next...

An interview with Manchester based art collector Connal Orton, who works as an Executive Producer in television, making comedy and drama programmes for children. He previously worked as a theatre director, specialising in first productions of new plays.